June 6th, 2013

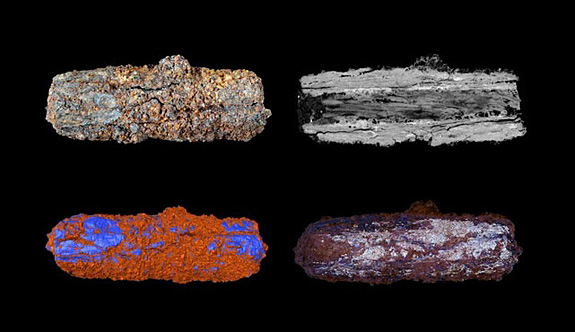

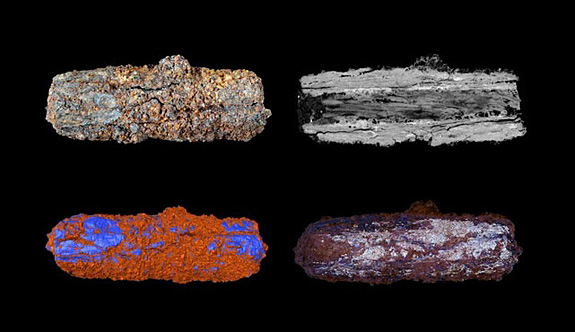

This rusty tube-shaped bead may not look very impressive, but its chemical composition reveals that it was part of a meteorite that ancient Egyptians crafted into iron jewelry more than 5,300 years ago.

Egyptians of 3,300 BC probably believed that the sky-born metal was a gift from the gods, according to scientists from the Open University and the University of Manchester, who studied the artifact using an electron microscope and X-Ray CT scanner.

A chemical analysis revealed that as much as 30 percent of the metal inside the bead was composed of nickel, which strongly suggests a celestial origin. Nickel-rich iron wouldn't appear in Egypt until thousands of years later during the Egyptian Iron Age.

The scientists also created a 3D model of the bead's internal structure, which revealed that the ancient Egyptians created the ornament by hammering a fragment of iron from the meteorite into a thin plate and then bending it into a tube. Their findings were published in the May 20 edition of Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

“The sky was very important to the ancient Egyptians,” said Joyce Tyldesley, an Egyptologist at the University of Manchester, UK, and a co-author of the paper. “Something that falls from the sky is going to be considered as a gift from the gods.”

The bead studied by Tyldesley and her team was one of nine metal tube-shaped beads that were first excavated at the Gerzeh cemetery near Cairo in 1911. The iron beads' inclusion in burials suggests this material was deeply important to ancient Egyptians, perhaps ensuring the deceased a quick journey to the afterlife, the scientists suggested.

In 1928, scientists studying the composition of the beads first suspected their cosmic origin. They determined that the nickel content was unusually high—the signature of iron meteorites.

But then in the 1980s, other scientists countered that the nickel-rich material could have resulted from early attempts at smelting.

The latest data puts an end to the mystery. The bead demonstrated a distinctive crystalline structure called a Widmanstätten pattern. This structure is found only in iron meteorites that cooled extremely slowly inside their parent asteroids as the Solar System was forming.

The beads are currently part of the permanent collection of University of Manchester’s Manchester Museum.

Egyptians of 3,300 BC probably believed that the sky-born metal was a gift from the gods, according to scientists from the Open University and the University of Manchester, who studied the artifact using an electron microscope and X-Ray CT scanner.

A chemical analysis revealed that as much as 30 percent of the metal inside the bead was composed of nickel, which strongly suggests a celestial origin. Nickel-rich iron wouldn't appear in Egypt until thousands of years later during the Egyptian Iron Age.

The scientists also created a 3D model of the bead's internal structure, which revealed that the ancient Egyptians created the ornament by hammering a fragment of iron from the meteorite into a thin plate and then bending it into a tube. Their findings were published in the May 20 edition of Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

“The sky was very important to the ancient Egyptians,” said Joyce Tyldesley, an Egyptologist at the University of Manchester, UK, and a co-author of the paper. “Something that falls from the sky is going to be considered as a gift from the gods.”

The bead studied by Tyldesley and her team was one of nine metal tube-shaped beads that were first excavated at the Gerzeh cemetery near Cairo in 1911. The iron beads' inclusion in burials suggests this material was deeply important to ancient Egyptians, perhaps ensuring the deceased a quick journey to the afterlife, the scientists suggested.

In 1928, scientists studying the composition of the beads first suspected their cosmic origin. They determined that the nickel content was unusually high—the signature of iron meteorites.

But then in the 1980s, other scientists countered that the nickel-rich material could have resulted from early attempts at smelting.

The latest data puts an end to the mystery. The bead demonstrated a distinctive crystalline structure called a Widmanstätten pattern. This structure is found only in iron meteorites that cooled extremely slowly inside their parent asteroids as the Solar System was forming.

The beads are currently part of the permanent collection of University of Manchester’s Manchester Museum.